U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry shakes hands with Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif after the P5+1 and Iran concluded negotiations about Iran’s nuclear capabilities on November 24, 2013 Photo: Wikipedia

Why has the US become so overtly aggressive towards Iran about de-nuclearisation after that country has apparently met international requirements that it limit its production of enriched uranium?

In many ways the current spat between the two countries is a metaphor for the way in which adversaries avoid facing up to each other directly in the Middle East today. That is to say, they use some secondary reason to argue about principles in the same way that a long-married couple might have the most terrible row about which end of the toothpaste tube should be squeezed. Or they might use a proxy to go into action of their behalf – again on the basis of some pretext that might not be the real grievance.

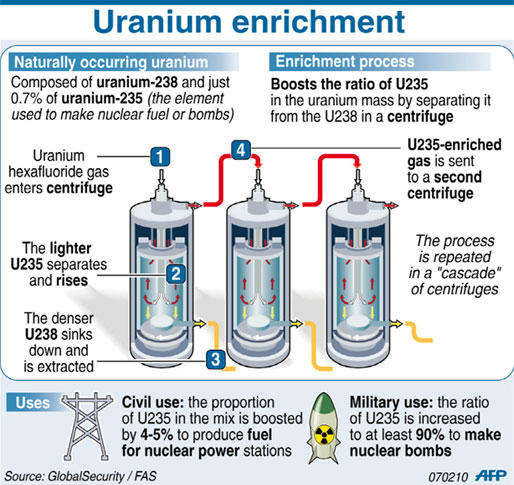

And so today, the US has decided to make an issue of what it claims is a series of breaches of a 2015 agreement called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), also known as the Iran Deal. Under the terms of that agreement, Iran agreed to cut its stockpiles of enriched uranium and to significantly reduce the number of centrifuges it operated (used to produce the enriched material).

From that date forward, and for a period of at least fifteen years, International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) inspectors were given access to Iran’s entire nuclear infrastructure and have spent thousands of hours monitoring and inspecting all relevant activity. Within months, those inspectors confirmed that Iran was in compliance and appeared to be fully committed to the plan.

In return, sanctions and other international restrictions on Iran’s ability to trade oil and other goods and services were relaxed. Indeed, it was generally regarded as one of the most important “peace deals” to have been struck in recent times. European countries in particular started to invest in Iran and many thought that this was a textbook case of long term economic benefits and interests bringing “rogue countries” back from the brink.

In March 2018, the IAEA reported that clearly stated Iran was in compliance.

In spite of this, and only two months after that 2018 report, President Trump confirmed that he would implement his earlier threat to refuse to ratify the Iran agreement when it came up for its annual review in the US, citing reports of an historic and undeclared covert nuclear facility that had not been reported back in 2015. In this he was apparently relying heavily on Israeli intelligence. (It should be noted that Israel had to some extent precipitated the whole Iranian nuclear deal when in 2006 it had threatened to bomb Iran’s fledgling nuclear installations.)

Mr Trump’s criticisms seem not to be borne out by the facts on the ground. As recently as May 2019 the IAEA again issued a statement that Iran was complying with the main terms of the agreement, although a rather loosely defined limit on centrifuges might need some closer scrutiny which could lead to additional checks on the ground.

A number of observers and industry “experts” have been openly scornful of Mr Trump’s views, citing the fact that Israel has its own “illicit” nuclear arms based upon an undeclared and, therefore, illegal enrichment programme. The same experts also point to another country that has an illicit enrichment programme, India. In neither case has the US expressed any serious concerns about these programmes; so why is it doing so with Iran?

The answer is most likely to do with the way Iran has been using its proxies in the Middle East to carry out acts of terrorism and open warfare, an example of which is its support for the government of President Assad in Syria. It is also strongly linked to Pakistan, and some believe this is part of the reason that the whole Afghan insurgency has been so problematic.

The US strategy in Afghanistan has been partly based on a determination to try and stop the take-over of Pakistan by a “fundamentalist terrorist government” who would then have control of yet another illicit national nuclear weapons programme, a prospect that worries many around the world. It is assumed that this is one reason that Iran has been so active in the region, as they might well be looking at acquiring a working nuclear weapon system in very short order from Pakistan.

In addition to all the above, there is the matter of Israel’s loathing for the Iranian state (not entirely surprising given Iran’s oft-declared desire to destroy Israel at some point), and their strong links with the US - and Mr Trump in particular; witness the recent announcement about the US Embassy being moved to Jerusalem. In addition, a more recent indication of Mr Trump’s close personal ties to Israel has been the naming of a new settlement on the Golan Heights as “Trump Heights” after Mr Trump officially recognised the Israeli occupation of the area (in spite of the fact that this has been declared illegal by the United Nations).

(In fact, this might be an example of yet another “proxy campaign” – but this time with the Israelis using the US to endorse various actions that have been condemned by the UN and other international bodies. That said, Mr Trump is delighted to do so as it, in turn, assists with his personal political ratings to bring support from the powerful Jewish constituency in the US.)

Once the US withdrew from the JCPOA it also re-imposed the old sanctions. However, in a move characteristic of the current President’s somewhat simplistic view of world affairs, the US promptly demanded that all other nations follow their example. In addition, it was declared that any company doing business with Iran thereafter would be pursued in the US courts and blacklisted from doing business in the States.

Faced with a choice between supporting the US or Iran, many countries have tried to steer a middle course, assuring the Iranians that they still endorsed the JCPOA, but not quite sure about an open confrontation with the US. As a result, and in the absence of clear and direct support from their parent national governments, many multi-national companies have had to make a hard business decision and withdraw from some extensive and expensive investments in Iran.

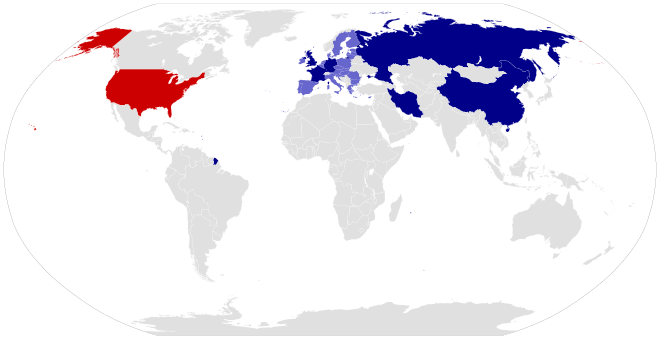

Blue: Current signatories of the JCPOA.

Red: Withdrawn signatories Source: Wikipedia

The Iranians, who initially accepted assurances from the likes of Europe about wanting to maintain the agreement and to keep trading, were increasingly faced with the reality that their foreign revenues were once again in decline. They not unreasonably asked for something rather more concrete in the form of a resumption of trading in oil etc. However, the Europeans pointed out that it would be almost impossible to fill the gap created by the unilateral US sanctions given the inter-related nature of global business. In short, the likes of Germany or the UK could not protect a company from US legal or financial punishment for breaking a US-declared embargo.

And so the Iranians started to talk about a deadline, effectively asking the rest of the world to ignore the US. They have been supported in their actions by the Russians and Chinese, but less so by the likes of European countries who have been trying to maintain their precarious seat on the fence. In order to ramp up the pressure, the Iranian government then declared it would treat the JCPO Agreement as defunct and start to enrich material regardless. It is, after all, just about the only card they have to play with the West – or almost.

This is where the tanker-attacks come in - at least according to US claims. The Iranians are supposed to be taking it out on the world oil trade, driving prices up and destabilising the supply of fuel by attacking tankers. Reports suggests that limpet-type mines have been remotely detonated on the hulls of ships, or that missiles of some sort have been used (crew members have reported seeing fast –moving incoming objects just before hearing explosions).

The US has also revealed video evidence of what was described as a small Iranian naval vessel alongside a tanker, with the crew removing an un-detonated mine from a hull. It is not totally clear whether this constitutes hard evidence that the Iranians put the mine there in the first place – though some say it was a dud and had to be quickly removed before the US got hold of it.

The critical question regarding these attacks is the geographical location where the explosives were actually attached. Some argue that only the Iranians would have the ability to do this so close to the territorial waters. However, others point out that it is almost impossible for someone to attach them to a moving ship – so they could have been attached many days before, when the tankers were taking on their cargo or even going into some other port for bunker oil. However, this last suggestion poses the obvious question as to why crew members would not have spotted the devices before they went off.

Tankers are large vessels in the main, and are operated by small crews. As has been shown in studies of pirate-attacks off the Horn of Africa, it is possible for small vessels, such as fast-moving skiffs, to get quite close to a modern ship with being observed, and once under the stern they can enter a radar dead-spot. That said, it still does not properly answer the question about how the mines were actually attached to the hull of a moving ship - unless it merely require a strong, determined person with a magnetic mine on the end of a long pole.

The US was a key proponent of the JCPOA when the Obama administration was keen to try and address the Iranian question. Obama was somewhat less beholden than Trump to the Israeli lobby and pushed the agreement though in spite of their strong objections. Today, with a more aggressive, overtly pro-Israeli administration in place, and with the recent events in Syria as a backdrop, the US strategy has changed.

It might also be that Mr Trump, apparently foiled in his attempt to denuclearise North Korea though diplomatic sweet-talking, is determined to try and save face by taking a more blunt approach with Iran. Whether or not he has the will and political power to take it to the point of military action is now a matter of great concern to all of us, for open warfare with Iran has the potential to make Iraq or Syria look like dress-rehearsals for a very much more dangerous regional (or indeed global) conflict.

Comments on Why is the US so aggressive towards Iran?