Recent news about the possibility of a war-crimes investigation into the killing of four young men in Afghanistan raises the spectre of many more inquiries where relatives or people who knew the victims accuse the British of such crimes – or does it?

Given that the matter of the four people allegedly killed in cold blood in a local base is under some sort of judicial review, it would of course be wrong for TMT to attempt to assess what went on. In addition, we do not have any more of the facts than anyone one else out there – apart from the troops in the room at the time.

That said, we in the West do tend to have a rose-tinted view of the world that makes us take a rather tough line on such matters: it also makes us victims in a way, as we are frequently exploited by those whose own standards of behaviour generally fall far below those we impose upon ourselves.

A few years ago, a BBC radio news item sought to provide proof of how harsh the British approach was (and is, presumably), to the matter of child migrants caught up in the problems of crossing Europe on their way to this country. The reporter went to an Italian camp for children and asked the manager to select two youngsters who were asked to tell their stories. Their comments were prefaced by the manager asking us to imagine how awful conditions must have been at home for their respective parents to have sent their children away to safety on their own.

The first child was a young woman who came from West Africa and explained that she wanted to be a hairdresser and decided that her career prospects in Europe would be better – so she and her family paid a large amount to smugglers to get her to Italy. The second was a lad of fifteen who said he came from Cairo and wanted to be a football player: so his parents paid $5,000 for him to get to Germany.

Seemingly, neither the camp manager, the BBC reporter, or the programme editors questioned the details of the stories. Neither person was trying to get to the UK, and neither came from a country deemed to be dangerous. Neither had been forced out of their homes, and in both cases their parents had willingly paid for their children to make the journey on their own to pursue a career ambition.

Imagine what would have been the public response if British parents had sent a fifteen year-old to the States via illegal migrant routes in order to become, say, a film actor. A custodial sentence would have almost certainly been the result.

However, their stories have another message that we need to consider very carefully in the West. It is that our standards are not universal or absolute. When is a child an adult? Is it 21, 18, or indeed 16 as some now insist? Is it when you are allowed to fight and die for your country, drink a glass of beer, or vote in a general election? Or is it up to local customs and tradition to decide? In the UK, for example, a migrant presenting themselves as being under 18 could remain in the care of a local authority’s childrens’ services when they are well into their twenties.

Some countries would be astonished that we regard a person of seventeen and a half to be a “child” still. In some of those places, people of 14 or younger are married, having children and generally playing an active part in the support of a household and raising children. They are effectively independent members of society – albeit in most cases within the highly supportive environment of an extended family.

In many countries the necessity for young people to contribute to the family’s finances trumps any considerations about lost childhood or the like. The same applied after WW2 when many young people in Germany were orphaned and had to survive in a very harsh world. This could lead to a feeling that children should never be exposed to such experiences, but also a belief that children are a lot more capable than we allow them to be today.

A few years ago, a German friend left her son with his grandfather, who allowed him to wander off. She was utterly distraught and called the police. The grandfather was puzzled by the fuss, explaining that, at the end of WW2 when he was the same age as his grandson, he had led 40 boys, all younger than him, in a 150 mile trek across hills and mountains to surrender to the Americans rather than the Russians. The missing grandson turned up soon afterwards having cleverly worked out how to get back to the chalet. He was immensely proud of his achievement and explained that, after his initial concern, he just got on with finding a way back.

There will of course be many who dismiss the valuable learning experience that lad went through, arguing that nothing justified putting the child at risk of predators and/or accident and injury. For this is what modern society in the West has become: a society where no stone should be left unturned to reduce or even eliminate any form of risk. Sadly, our young seem to learn fewer and fewer lessons about the real world, and so actually run the risk of being harmed by things for which they are wholly unprepared,

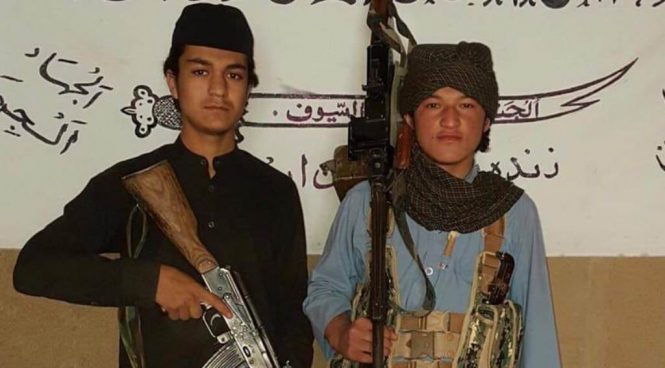

And so back to those four young people allegedly shot by British SF troops. How young or old do you have to be to be a combatant these days? If you were to see a person in a suicide vest approach your mates, would you hesitate to shoot if they were obviously very young? Would you rather sacrifice your chums than be caught up in a row about whether you had committed a war-crime? For that is what we are sometimes asking of our troops, who themselves might be as young as 18 or 19: to be able to make snap decisions, in life or death situations, that will stand up to detailed and lengthy scrutiny by learned people (and some not so learned) in the comfort of a courtroom in the UK or the Hague.

Who knows what happened that day when those four were shot? But for anyone to argue that the victims were incapable of having been members of the Taliban, or that they could not have been involved in any acts of violence by virtue of being younger than 18, is so utterly daft as to be risible.

That having been said, the British Forces have an enormously high reputation around the world for fair and decent behaviour. If, for some reason, those standards were compromised, and the four were indeed killed in cold blood whilst bound or in captivity, then a crime would indeed have been committed. It would also be a matter of great shame to all who either have served, or serve today.

We can only hope that any inquiry into the incident is fair and takes into account all the circumstances of the time, place, and realities of what goes on in that tragic country.

Comments on The killing of four young Afghanis