On the Forces Network website there is a fascinating article about the work of the Allied Military Missions which spent days and weeks deep in the heart of the old East Germany, looking for Warsaw Pact troop-movements, new equipment and other intel. The piece is well put-together and a reminder of what we used to get up to in the “Bad Old Days”. However, there is another, admittedly less glamorous, story to be told about the Flag Tours which were carried out in East Berlin by Allied officers from the Western Sector of that city.

Flag tours were ostensibly all about showing the flag, re-affirming the rights of the four powers to go anywhere in Berlin without hindrance from the two national German states. In reality, the tours, carried out by small teams of two, often in Range Rovers or ex-Brixmis Opels (driven by soldiers from 62 Tpt Sqn), were used to gain intel about Russian and East German military assets in and around East Berlin. This included watching various barracks and installations, but also trying to spot convoys on roads as well as military-train movements on the edge of the city boundaries.

Unlike Brixmis, Flag Tours were not allowed to leave East Berlin and had to turn back at the signs denoting the edge of the city: signs that were sometime deliberately moved back or even removed entirely to trick us into going into East Germany-proper so that we could be stopped and held pending high-level discussions. For this was all part of the game that was played between the East and West in those days, and the most aggressive actors were the East Germans who, in spite of having no legal authority to do so, used to give Flag Tour teams a hard time once they had caught up with them.

Flag Tours were carried out routinely by all sides. Lists of tour dates were issued to British units in the West and an officer was detailed to carry them out once they had been registered for such duties. On the appointed day you would either go to the main HQ in the Stadium and meet your driver and vehicle, or by arrangement a car might come to your barracks, or even your married-quarters if you were going over at some ungodly hour.

Non-routine tasking might also be issued once the main HQ knew that you were reasonably familiar with the East. These tours might be the result of a Brixmis tip-off such as news of a missile train passing though the East German rail network to the north of the city, a spider’s web of rail-tracks which radiated out to the whole of East Germany and which made it relatively easy to get eyes-on for many rail movements.

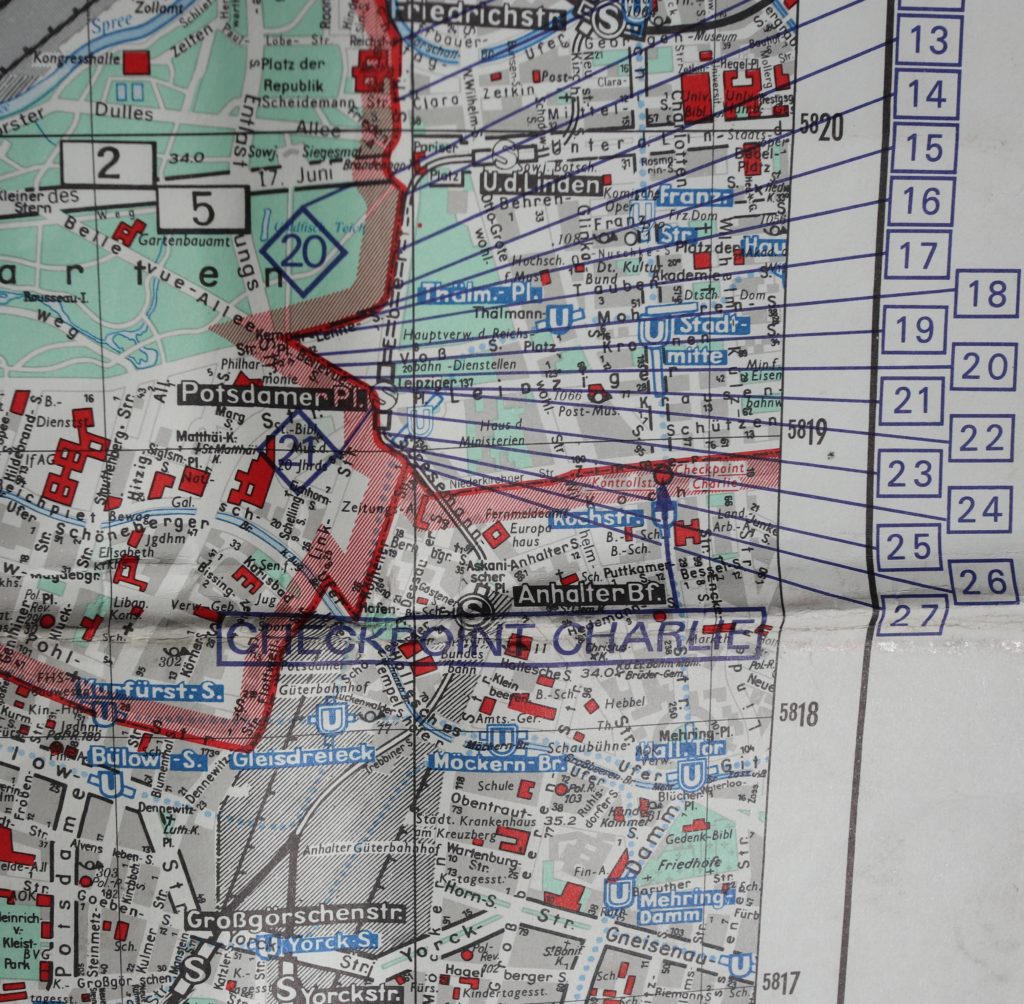

In such cases, it was not unusual to be given a time by which you had to be in position on a bridge or high-point from which to observe the target. This in turn sometimes meant you had to meet the driver and vehicle somewhere in the West and then literally stop a police car and get them to blue-light you to Checkpoint Charlie. Those cars had a gadget that turned traffic-lights green and it was great fun to whizz through the city “on a mission”! The sirens and lights were always turned off a few hundred yards from the crossing to avoid alerting the border guards who might then deliberately take their time allowing us through.

All British Flag Tours had to go through Checkpoint Charlie and we got to know some of the guards quite well. That is not to say we were allowed to speak to them as they were East German and had no authority over us. Indeed, it was in standing orders that we were not allowed to acknowledge their authority and certainly not to obey an order from them. That said, there were one or two older guards with a sense of humour at least. One of these had obviously been ordered to take a closer interest in us one day and kept circling the car. After a while I opened the window a crack and he stopped to ask me my rank (I had a coat over my working-dress as I knew we would be standing outside that winter’s morning). Breaking all the rules I replied “General”, at which he smiled broadly and saluted saying: “Jawohl Herr General, wilkommen in der DDR ”; he did that every time I passed through thereafter.

The amount of photography and data collected by the East at the Checkpoint Charlie crossing was of pretty doubtful value in reality. They must have seen the same vehicles and drivers hundreds of time. The officers less so – but we were not exactly John Le Carre material! More likely, it gave the East Germans time to whistle up an MFS Car to follow us around in the East. The Ministry for State Security (Ministerium für Staatssicherheit), were almost invariably in Mazda 323s, usually painted a pale blue or grey. There was only one person in the front as the passenger seat was fitted with a red box or two which was their special radio system. They usually had a hi-tech cover over this in the form of a newspaper.

The paper also doubled as a personal camouflage outfit. On occasions, when we were bored, we would stop suddenly, forcing the MFS car to draw up behind us. One of us would get out and walk back, around the car, and the MFS driver would pick up the paper and hold it up to cover his face, moving it around his head as we walked around. So two of us would then get out and walk either side of the tailing car, forcing the driver to wrap the paper around their head. That allowed us to take a good look at what he had in the vehicle – including that radio of course; it never amounted to much, though. It was a school-boyish prank – but amused us greatly and could lighten up a dull day.

Travelling to the East was strange but exciting at times. The first thing that hit you as you crossed over was the smell. Brown coal was a staple fuel and heaps of compressed briquettes lay in the streets where it had been dumped for collection by households. When burned, it created a brown smog that hung over East Berlin on still winters’ days. This combined with the stink of two-stroke exhaust spewing out of inefficient cars like the Trabant and Warzburg left you with a sore throat and streaming eyes at the end of the day. Those little cars littered the streets – literally in many cases, as some back streets had more wrecked vehicles sitting on flat tyres than working ones.

Everything was remarkably drab. It was apparently due to a lack of paint pigment – but the effects were made worse by the dirt from pollution that seemed to coat everything, as well as a sticky brown concoction that was used to protect metal against rust. That said, rust was everywhere: lights, fences, gates, traffic signs; they were all rusty, tatty and generally mean. Even when paint was provided, it was clearly pretty third-rate stuff and usually applied in such a crude manner by almost totally disinterested state workers that it hardly made any difference.

We were once tasked with spotting a missile train and had to wait on a hill for a few hours. After being mobbed by the East German police we were left alone and, with nothing else to do, studied a bunch of workmen laying gravel or ballast on some tracks about half a mile away. They did almost nothing in that time, only stirring themselves when a dark-blue Trabant bumped along the track to check them. As soon as it left, they returned to their previous state of inactivity. It seemed to us to sum up the whole problem of the East.

(When the train came through we had to laugh as the carriages were “disguised” passenger wagons. That meant that someone had painted pictures of happy travellers in the windows, behind which the missiles were carried in special containers: bright and smiling, healthy, happy people frozen in mid-wave or deep conversation. The effect was rather like those old tin toys with painted people in shop windows, cars and model railways. It was another wonderful example of just how basic things were in those days. In fact, the disguise was probably intended for local people more than us - or perhaps it was just part of their overall propaganda to get people to think they were in a socialist nirvana.)

Driving Range Rovers had a major advantage in that we could see over all the local vehicles other than lorries. It also meant that we could spot the tails, and we sometimes turned off the road to cut across a patch of rough grass or parkland to lose them. Occasionally they would gallantly give chase and the sight of those little Mazdas bouncing around before getting stuck in a ditch or a patch of mud still makes me smile.

The Range Rovers attracted interest wherever we went as they were so obviously bigger, better and more powerful than anything the locals drove. Occasionally we stopped for a drink and bite to eat and were then surrounded by youngsters who were very nervous about approaching too close for fear of informers ratting on them. We used to throw sweets and chocolate bars to them – and roll cans of proper coke which they would grab and make-off with (the local brand was called Prick Cola, a foul-tasting brew). Even an empty Pepsi or Coca Cola can was a valuable prize to those children.

We frequented a few shops that sold some decent toys (mostly train sets), and porcelain. But we had a long list of items we were not allowed to buy for fear of depriving the East Germans of important staple products: curiously, the list included wall-paper glue. We used to give the owners of some shops small presents of luxury soaps and the like, but any attempt to offer western money was quickly turned down as they were afraid to be seen accepting currency as it might suggest an intent to escape to the West.

Collecting trains and porcelain figures became something of sport and duplicates were often traded with the Brixmis guys who had access to many more shops throughout East Germany. That said, I managed to find one very rare model of an HO-gauge loco and still slightly regret to this day trading it with a very jealous Brixmis captain. Boxes of unused Piku and Berliner Baren OO, TT and N-gauge railways are still sitting in our attic over 35 years later; most of the china birds are up there as well!

As already mentioned, the VOPOS (Volks Polizei), could be quite aggressive – but it was almost always a load of noisy barking with very limited bite. Some merely went through the motions, shouting and haranguing us for the required 30 minutes, getting in our faces and taking dozens of notional photos, and then putting everything away, smiling at us and saying “have a nice day”, before returning to their cars and driving off.

The Russians were slightly different. Most of the time we did not bump into them, but when we did, things could go seriously wrong. This was almost invariably due to the fact the average Russky had never been briefed about the likelihood of meeting a Brit or American and so when it happened their reaction was one of surprise and, most likely, fear. Minor incidents included being boxed-in by their Gaz 66 trucks and then covered in a blanket so that we could not observe a convoy or whatever. If we did meet a convoy on the move, it was usually early in the morning and then the reactions could be rather more violent, with a tracked APV or tank being used to force our cars off the road.

On one occasion, a Flag Tour vehicle was forced off the main road into a side street where they tried to run around before hitting the city boundary. In the process, they reversed into a small but deep pond and got stuck in the mud. Immediately a Russian platoon-commander ordered his men to surround the vehicle. Some thirty young soldiers de-bussed and half of them waded out into the pond, pointing rifles with fixed bayonets at the Flag Tour team. It must have been awful for those young Russians as it was winter and the pond had been covered in a layer of ice before the vehicle broke through it. They stayed there, unwavering, for 45 minutes, at which point the situation was sorted through diplo channels.

The Russians were often a sad bunch. Young soldiers on guard duty that we occasionally walked by in the depths of winter were frequently dressed in threadbare greatcoats with ragged hems which had been crudely shortened with a knife. Their shirts were equally thin and usually dirty, and you could see that many of them were wearing boots with holes which had been stuffed with paper. Their faces were a picture of misery: red cheeks, blue lips and runny noses – about which they could do nothing when they were on guard. They stood outside their utterly run-down camps with rusty gates and fences and cracked walls. Occasionally we would see soldiers painting a wall or even a pile of coal white: we were told it was a punishment duty and that the coal was painted to stop people stealing it; as with so much of the East in those days, the paint-finish was not exactly brilliant!

The Russians were a good source of information for a number of reasons, not least being the fact that they drank a great deal and had a generally lax approach to security , leaving that side of things to the East Germans instead. They were also short of many basic items, including loo-paper. So they used anything to hand, including old note-books. This resulted in trips to various pits where waste, including sewage, was dumped outside the camp. At one such place, we just had to wait till the huge tipper-lorries had made their regular run to dispose of thousands of empty drinks bottles before hopping across a fence and looking for the tell-tale signs of military note-paper. The end results were scraps of thoroughly unpleasant paper, which, when dried and scanned with a magnifying glass, revealed intelligence of stunningly limited value!

Given the Four-Power Status of the city, both East and West, we had almost total freedom to wander where we wanted. That said, we took the job seriously in the early to mid-1980s and being in the East made you feel that everything we were doing was worthwhile. We did not want to be overrun by a regime that managed to reduce East Germany to the dreadful state it was in, compared to the West at that time.

We felt quite sorry for the ordinary East Germans who used to watch us eat when we went to a café or “schnelly”. They had a sense of deprivation about them that really did make you feel guilty about how good we had it in the West. However, that was not the case with the East German army which we sometimes saw on exercise and also on their big parades. Then they were not in the least pitiful, but were instead a highly impressive machine that oozed self-confidence and inspired not a little fear as they marched in close-order block of several hundred men through the streets singing and shouting their socialist battle-cries. It was very impressive.

In one curious incident, we had been on a helicopter border patrol and after looking at the photos we had taken we noticed that there had been a lot of work around the site of Hitler’s old bunker, with masses of fir trees heaped up in the middle. On a Flag Tour the following morning, we diverted by the site and saw that a gate had been left open in an otherwise screened-off compound. We walked in and were astonished to see the trees had been pulled aside to reveal the bunker looking remarkably good after decades under the earth. It was as if time had stood still for everything was exactly as it was when the war ended. We took some photographs in spite of being shouted at by half a dozen guards and workers. They might well be the last -or only - shots taken before the East Germans started to demolish everything above ground.

At the end, it was clear from the sort of material we saw in shops that the East German state was trying to re-establish a sense of national history and even independence from a Soviet Union that they thought was showing signs of collapse. From what we saw, had there actually been a war, it would have been the East Germans who would have been the hardest opponents to overcome, a suspicion since confirmed by recent visits to museums in what was the former East Berlin, “Haupstadt der DDR”.

It is hard to say how useful the Flag Tours were in reality. Yes, they made a point about all Four Powers having access to the city as a whole, and perhaps they provided some reasonable intel at times. But possibly their most valuable contribution was to at least let the East German people see that we were a reasonably friendly bunch and to provide them with some glimmer of hope that their world might eventually develop along similar lines to ours. Whether that was a good thing in the long term remains to be seen. Time will tell.

(For a fun account of some earlier Flag Tour escapades see this link: http://www.armytigers.com/stories/berlin-1970-72-%E2%80%93-young-officer%E2%80%99s-tale-flag-tours)

All photos from author’s collection: copyrights retained.

Comments on Remember the Flag Tours in East Berlin?

There is 1 comment on Remember the Flag Tours in East Berlin?

Comment by Nigel Dunkley

Great to be reminded of the good old bad old days by Murray’s excellent article here!

We were good friends when he and his wife were on the Berlin staff and I was doing a tour with Brixmis. We also shared a love of East German toy trains so seeing these photos of his have stirred many memories!

Thanks Murray - Berlin got so under my skin I eventually did three different tours in three different ranks and am still here in Charlottenburg - as are the trains!

Handpicked links