TMT is publishing a series of short, historical accounts of National Servicemen who were awarded the GSM while serving in a variety of places such as Malaya, Kenya, Korea and Cyprus. The pieces have been produced by Roger Brown, who got his own GSM as a National Serviceman in Cyprus between 1957 - 59.

If any of our readers would like to submit their own experiences along a similar line, then please do get into touch with TMT.

When writing to us please do not use the subscription tab to send a message: instead, please use the “Contact Us” email address which is: [email protected]

Part 1: Iain Morrison in Kenya

Iain Morrison was born in Kenya in 1937 to parents who were long established Kenyan settlers. The family lived in Mombasa on the east coast of Africa and Iain went to secondary school at St Mary’s, Nairobi where it was compulsory to join the Combined Cadet Forces (CCF) and be taught parade ground drills, proficiency in small arms and basic infantry tactics. During his early years, his ‘nanny’ was a local Kamacia man who spoke Swahili to Iain, thus Swahili became his first language which proved very useful during his National Service years.

As Kenya then was part of the Commonwealth, all men of 18+ years had to do their National Service, so late 1955 Iain received his Kenyan Regiment ‘call up’ papers and, in January 1956, he reported to the Regimental Headquarters in Nairobi. Once in the Regiment, Iain undertook 3 months basic infantry training by British NCOs and Officers at Lanet near Nakuru. 6 months was the norm but due to the increasing activities of the Mau Mau, training was cut to 3 months.

Basic training was very intensive, the squad learning drills: weapon training; deep forest warfare: map reading and basic thick forest survival skills. There were 4 squads of about 30 soldiers each. Two Companies were based at HQ Nairobi- ‘HQ’ Coy. and ‘O’ (Operations) Coy. Iain was assigned to ‘O’ Company and spent 4 months patrolling in and around Nairobi and the Aberdares looking for Mau Mau and their sympathisers.

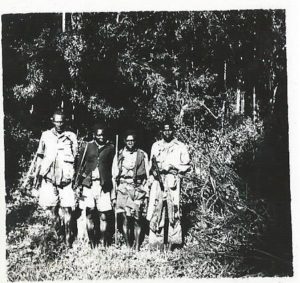

Each patrol lasting between 3 to 14 days, comprised 6-8 men (with an occasional tracker) carrying .22 rifles with silencers:Sterling sub-machine guns:FN rifle (later known as the SLR): Mark 5 Lee Enfield rifles with flash hiders; hand grenades and ammunition. They also had to carry their own sleeping bag, water, and rations. Patrols invented their own methods of hunting terrorists and took the battle to the Mau Mau territory in the high altitude bamboo forests and lands around the Aberdare mountains and Mount Kenya.

Every man in the patrol had to be able to kill silently either by knife, hands or rope, and all carried a length of cord for securing prisoners. It was important that each man should know exactly where all his equipment was; for instance that his torch was on his left, handkerchief in his right pocket etc., because any movement had to be swift and silent, equally a voice or sneeze would carry far in the forest. Hand signals were used for communication, and sometimes, when moving in the dark, a patch of luminous paint on the back of the man in front helped to keep contact when following in the dark along a forest track. Frequently the patrol would halt and move of the track and carry out a security check behind them in case they were being followed.

Constant vigilance was needed however tired the patrol was in order to cope with a charging wild animal or, more importantly, a burst of gunfire from a hidden source. Patrols often followed tracks through the dense bush created by the wild animals living there and there was always the danger of disturbing them. Quite often patrols were charged by buffalo who had been injured by the bombing from Lancaster bombers.The severe heat combined with the altitude was very conducive to sleep during the daytime whilst night were often tense and sleepless, but to give in and doze on patrol could cause the patrol to loose contact with a possible terrorist gang and leave the patrol vulnerable to attack.

If a patrol had been out in the forest for a long period of time, suffering the hot days and freezing nights, individuals could suffer sleep deprivation, experience hallucinations, and become short-tempered. It was imperative that the patrol worked together and it was incumbent on the leader to develop the skills and understanding to handle any problems that might arise during the time they were in the forest. A patrol leader once commented:

‘We weren’t allowed to wash, weren’t allowed to clean our teeth, we had grown beards and smelt terrible at the end of the three weeks but it was the only way to combat the chaps we were trying to catch, who smelt even worse!’

This was a most important point: smoking, washing, shaving, talking- all the daily habits one takes for granted in normal life had to be abandoned in the forest.

Private Iain Morrison, whilst enduring four long months of continuous patrols, never made contact made with the Mau Mau. On his return with ‘O’ Company to HQ, he was seconded to the Police Special Branch as a Field Intelligence Officer with the equivalent rank of Captain. His first posting was Nyeri, where his ability to speak Swahili proved an asset when working with Kikuya informers for information to pass on to the Police Special Unit or local Army units.

When at Nyeri he would ask the Mau Mau prisoners the following question:

‘Which of the Security Forces did you fear the most?’

The answer was:

‘The British troops washed in perfume, their tin cans rattled, they could be heard and smelled two or three miles away, but the Kenya Regiment never washed. They left all their equipment in one place, patrolled quietly and were good trackers. They walked through the forest like us; that wasn’t fair‘.

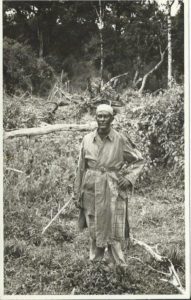

From Nyeri, Iain went to Kanja Prison camp near Embu. There he lived in the prison and was again interrogating Mau Mau prisoners for information to pass on to the Police and Army. At this point it was decided that he should go ‘under cover’ and become the leader of what was then known as a ‘pseudo gang’. A ‘pseudo gang’ comprised a small number of trusted ex-Mau Mau Kikuyu with a white policeman gang leader. The leader would be ‘blacked up’ and, in some cases to be more authentic, lemon juice would be squirted into their eyes to further give the impression that the ‘gang’ was all native Kikuyus, as their eyes were tinged slightly yellow. The ‘gang’ would wear native dress or skins and disappear into the thickly forested areas for weeks, living off the land, to make contact with the Mau Mau.

The concept was that if the ‘gang’ met up with a Mau Mau group they would try and persuade them to surrender. But if they refused, the ‘gang’ leader would produce from under his native dress a Sterling sub-machine gun and either the Mau Mau would then surrender or there would be a short sharp fire-fight.

Mount Kenya, with its thickly forested slopes was a natural refuge for the Mau Mau and under the thick forest canopy there were tracks known to be used by the terrorists for moving around, or driving stolen cattle along it to their hide-outs. There were also many wild animal tracks created by elephants, buffalos and other wild animals. Partially around the forest area, and within the Embu area, was a deep ditch called the Irangi. The ditch had sharp stakes embedded in its base, this formed an effective barrier in protecting local villages against the Mau Mau and wandering elephants.

If it was known that there was terrorist activity in the Mount Kenya area the Police General Service Unit or other emergency service would go in. If was deemed that the ‘pseudo gang’ should go into the forest the Army and Police would stay out of the area in reserve.

It was once suggested that the ‘pseudo gang’ should leave the forest first, report to the Army or Police who would then go into the forest. But, as someone said, seeing a group of dirty, smelly Kikuyus emerging from the forest after being on patrol for days or weeks, who would recognise them as ‘friendlies’? The idea was quietly dropped.

Iain was a member of the Police Special Branch for 18 months and, rejoining the Kenya Regiment at the end of his National Service; he reverted to the rank of Private.

Words and two lower images courtesy of Roger Brown.

Article copyright: Roger Brown

Comments on National Service stories Part 1: Kenya