An 8th January article in TMT, “MoD looks for a new way to recruit”, considered the problem of how to restore interest in the Army from the viewpoint of recruiting strategies and materials. The somewhat gloomy situation with regard to numbers has, however, been confirmed in the government’s own figures in its recently-released report “Quarterly service personnel statistics: 2019”, published on the 21st of this month.

Just to confirm the remit of the report, “This is a quarterly publication containing UK service personnel statistics on strengths, requirements, intake, applications and outflow. It replaces previous MOD tri-service publications including the monthly and quarterly personnel reports.”

As a whole, the Forces are down some 4,200 in overall strength since this time last year, a drop of 2.2%, and currently stand at 190,750. The figure for Full-time Trained Strength for the RAF, RN and RM, as well as the Full-time Trade-Trained Strength of the Army (note the difference in definition), is put at 134,990, a decrease of 2,270, or 1.7%; the target figure was 144,200.

The Forces have a “Workforce requirement” figure which forecasts the number of personnel needed to meet the demands of anticipated commitments as well as to maintain the training and support base. The shortfall in numbers meant that the difference between the Workforce requirement figure and actual numbers increased by 1% to 6.7% in the year to January 2019. This is important, for it means that “overstretch” is potentially going to get worse unless the Forces reduce their commitments – something that seems unlikely given the current Defence Secretary’s plans for “Global Britain” post-Brexit.

The Army, the largest employer of personnel, is most vulnerable to the sorts of demographic and similar factors which reduce young people’s interest in a career in the Services. In 2016, in response to what seemed like an almost impossible task to increase numbers, the Army decided to adjust its definition of trained soldiers to allow those with only Phase 1 training to be deployed in the event of a UK crisis. That is to say, those with Basic Training under their belt were deemed to be soldiers, with their Phase 2, Trade Training reckoned to be non combat-essential. By removing the requirement to have completed Phase 2, it was hoped that the Army could meet the 2015 SDSR’s target of 82,000 trained personnel by 2020.

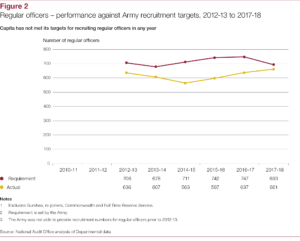

However, since that Review, recruiting has fallen fairly consistently. At the end of last year it was being reported that the contract placed in 2012 with the outsourcing firm, Capita, had not produced the necessary goods and that the Army was 5,000 short of the planned figure of 82,500 by the end of 2018.

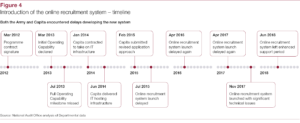

A number of critics pointed at the failure to get a new recruitment website up and running. According to the National Audit Office, it was well over four years late and had tripled its costs. The NAO added that it was now almost impossible for the Army to show any cost savings by having contracted Capita. As a result, many asked Gavin Williamson to carry out his threat to sever the contract with Capita if they continued to fail to meet their targets; however, he has not done so.

Part of the reason is that the NAO also found that the Army had failed to set up the necessary infrastructure needed by the new website. Presumably, therefore, a backroom chat with Mr Williamson established that Capita would be a tad upset about any early termination of its contract. The result is that they will “soldier on” till the contracted date of 2022, by which time they say they are confident that they will have caught up with their recruitment-targets.

Where does that leave the army today?

Following this eight-year fall in recruitment, the Army’ Full-time Trained Strength stands at just over 79,000, as against the target of 82,500. However, the Trade-Trained Strength is of course lower, some 75,880 as of January this year. So, according to the 2015 SDSR definition of what constitutes the effective strength of the Army, we are in fact some 9,000 short, which in percentage terms is just over 10%.

The dropping of the requirement that soldiers be Trade trained before being counted is worrying. The then CGS, Nick Carter, was forced to make the change for a number of reasons, but the one factor that might have been lost in the debate was that of the changing nature of the threat we face as a country. The rapid increase in the level and type of sophisticated threats, from IT systems to smart weaponry mean that the basic skills of soldiering (which produce, in simple terms, a bayonet strength), have been replaced by the need for very highly trained personnel, many of whom might not see the “sharp end” during their careers.

In other words, the army has a growing need for skilled drone operators, IT and signals experts, as well as intel-trained, counter-terror and other asymmetric-warfare ready personnel. Even down at the platoon level, troops go into battle with a plethora of electronic devices, all increasingly linked into, and dependant on, an integrated battle-management system. We have probably all read reports of troops in Afghanistan being saved not by guys with rifles and bayonets, but by the person in the corner with the laptop busily co-ordinating artillery DFs and airstrikes. This is the new reality.

It is inevitable that opposition politicians should start to jump on these figures; the Shadow Defence Secretary, Nia Griffith (someone whose career does not exactly lead to a presumption of having great knowledge of defence matters), has said that this points to the Government having:

“…..no plan whatsoever to stem this appalling decline. At a time when our country faces growing security challenges, it is simply unacceptable for the Government to be running down our Armed Forces in this way.”

This is of course silly political nonsense, for the world is not as binary as she would have us believe; to suggest that there is a deliberate plan to run down the army is plain daft. However, to have been seen to have presided over such a long-term decline in numbers does leave the Government open to accusations that they, or the Armed Forces, have let something slip on their watch.

It might be that the pay is not adequate, or that times have turned against military careers. Or, perhaps the younger generation no longer views the defence of the nation as being very high on its list of priorities. It has to be borne in mind that employment in the country as a whole is at an all-time high, with unemployment somewhere around 4%. This makes it even harder for the Armed Forces to tempt young people out of the civilian system, particularly as those same people have become very aware of the long-term implications of a late start to any subsequent career in civvy-street. (For this reason, some – rightly or wrongly, regard a technical career in the Navy or RAF as being somewhat less problematic than in the Army.)

Individual commentators have also pointed to the effects of Afghanistan and Iraq, where the rather less than glamorous realities of fighting an “invisible enemy” such as the Taliban have been well publicised in the press. Too many young people have been left with horrible physical and mental injuries to contend with for the rest of their lives; injuries which stand in stark contrast to the basic modern philosophy that everyone has a right to a cushioned life with “no-one left behind”.

Combine the above with reports of equipment deficiencies and other shortages in the field, and the sense that we do not look after our Veterans as well as we should, (although to be fair, that aspect of post-Service life is changing rapidly), and you have some very valid reasons for young people to question the merits of joining The Flag.

As is so often the case in this country, one gets the impression that the system is not properly “joined-up”. It is likely that overstretched military and civil servants would be very upset at the idea of it being suggested that they had not done a good job in the world of recruiting. However, the problems seem to have gone on for far too long for the MOD to be able reasonably to say that “the figures in the report are historical” to quote one recent official response.

The link to the MOD Quarterly service personnel statistics: 2019 is: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/quarterly-service-personnel-statistics-2019

Comments on Eight-year shortfall in Army recruitment