This article published on the Save the Royal Navy website on 18th July.

You’re the captain of one of Her Majesty’s warships and you’re on patrol in the Strait of Hormuz. The call you’ve been half-looking forward to and half-dreading comes through: there is a tanker under attack and you are to intervene.

You’ve been preparing your ship for this moment for over a year. You, personally, have been preparing for it your entire career. You are instinctively familiar with your ‘inherent right of self-defence’ and you have forensically studied the rules under which you may engage the enemy not in self-defence. You have probably done a Gulf trip five times before, but it was different back then. JCPOA was in full swing and “disciplined restraint” was the (US) buzz-phrase. The rhetoric from across the Atlantic doesn’t sound like disciplined restraint anymore. A ship has just been detained in Gibraltar; others were mined only a month ago. Your intelligence officer is busy trying to evaluate all this and determine what it means to you, right now. You know that if you are too aggressive you could take your country, and others, into a disastrous shooting war – not aggressive enough and your ship could get hit. You’re the captain now, it’s the middle of the night and this responsibility lies solely with you.

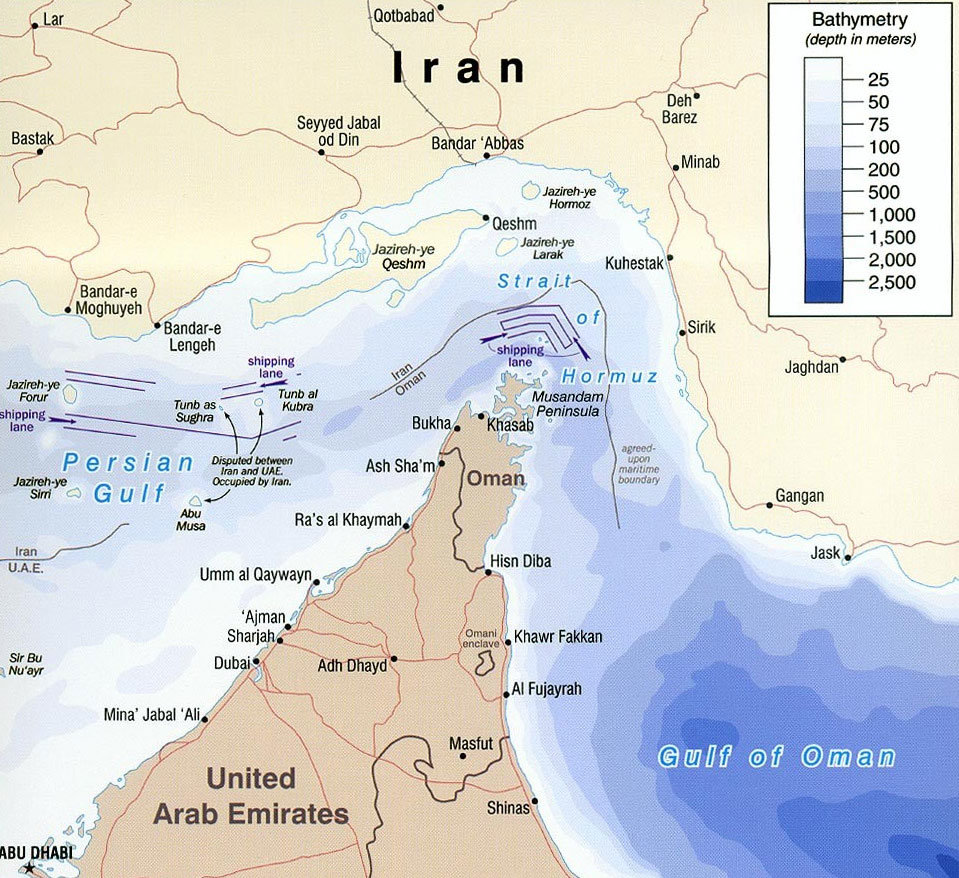

It’s worth taking a quick look at the lie of the land, as it were. The Strait of Hormuz runs east/west but in a curve round Oman. It’s approximately 21 miles wide, the same as the Dover Strait and almost as busy.

The Strait of Hormuz including traffic separation scheme (via Wikipedia)The United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) states that territorial waters (TTW) extend out to 12 nautical miles from the coast. Anything outside that is classed as High Seas and, in accordance with international maritime law, freely available to all vessels. Inside 12nms and you are in the host nation’s waters and with a few exceptions, you need permission to be there, especially if you are a warship. There are also restrictions on what you can and can’t do in terms of flying and operating boats etc. In cases such as Hormuz (Gibraltar, Bab El Mandeb etc), which are less than 24 miles wide, the TTWs therefore overlap. However, they require constant access so an International Strait is formed. There are still regulations as to what you can and can’t do in there but you don’t need host nation permission to enter as you would for territorial waters.

Within the International Strait there is also a traffic management system in place called a Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS). If you look at the purple band on the chart to the north of Oman there are arrowed lanes above and below – east to west on the north side and west to east to the south. All ships over a certain weight are obliged to use the TSS and there are very specific anti-collision rules for their use. To the western end of the chart, you can see more lanes, the northerly of which (for traffic heading into the Gulf) lies very close to Iran and is the subject of a whole other story. The point is that it’s busy but in a semi-regulated fashion. As a warship captain, this works in your favour because vessels that are not conforming or are behaving erratically are easier to spot.

The threat in the Strait can be broadly grouped into mines (sea and limpet), fast attack craft (missile, torpedo and suicide), submarines (conventional and midget) and missile (sea/corvette and land-based). These have all been specifically built and procured over a long period to defeat western conventional forces and be difficult to counter. This, they have achieved.The mine threat is very real as demonstrated on numerous occasions and they have the capacity and ability to close the strait very quickly should they so wish. They can also lay they them in patterns to direct your ship towards the fast attack craft threat – low-cost it maybe but it’s also sophisticated.

The Iranian Revolutionary Guard (Navy), the force that is directly accountable to the Supreme Leader, has upwards of two thousand fast attack craft. A single RN ship on its own and with no warning could defeat them into the low double figures, maybe a few more if the helicopter happened to be airborne. Any more than that, and you need serious back-up. They practice this kind of swarm attack very regularly.

This is what you don’t want to see

Then there is the lack of warning time. Let’s say a Bladerunner fast attack craft is coming at you at 30+ knots, even if you see it on radar the moment it leaves the coast and correctly classify it as threatening, you will have less than 8 minutes to engage. If you want to do this with the main gun and at range, much less. But how do you know it’s a threat at that range? Unless your intelligence is watertight, you don’t. This is whites of the eyes stuff and time is not your friend.

The Yono midget submarine is a particular menace. Often lurking just below the surface in the middle of the TSS they are armed with a couple of heavyweight torpedoes. These will kill a frigate and possibly even a carrier. There are always a couple at sea and they are hard to track and even harder to defeat.Finally, the missiles. Again, they have these in the thousands and many are on mobile launchers. These move about the coast on a regular basis conducting drills that to all intents and purposes are indistinguishable from an attack…and then they are stood down. Knowing whether or not this is a drill or the start of an attack is vital. If not, your time from detection, to classifying as a threat, to impact will be minutes, if not less.

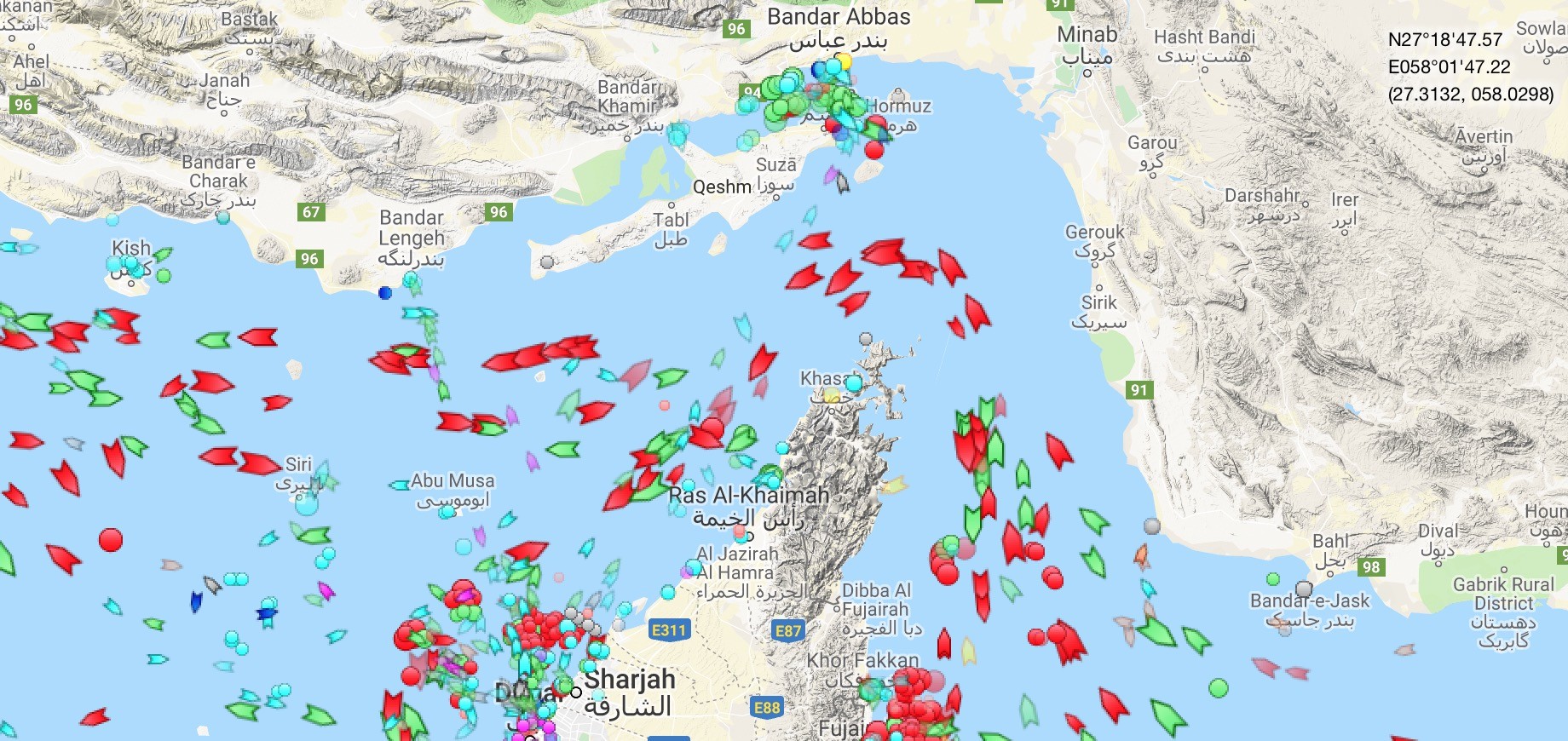

Random snapshot taken from Marinetraffic.com

Back in the Captain’s chair of HMS Montrose and you’re on route to assist the tanker. You wind-on the sprint gas turbines and head over there at max chat. You know full well that doing 30 knots immediately identifies you as a warship, no matter what you’re transmitting on your ‘system’. You also know that in a mine and submarine threat environment, that kind of speed makes you both blind and vulnerable. But you prioritise getting there as fast as possible – you have to. You call it in to the operations room in Bahrain to see who else is available if this goes south – has the US carrier got anything available that could make it to you in time? Do you take the ship to Action Stations (where everyone is closed up but takes a few minutes to get there, especially at night) or do you go with what you’ve got, i.e. all upper deck weapons manned but ‘only’ half the ship closed up elsewhere? You’re going to be operating very close to other ships at night so where is the best place for you to be – on the bridge (best spot for the tanker attack and fast attack craft) or in the operations room (for the missile threat)?

There are lights and ships everywhere. Most are in the sea lanes just going about their business, but many are not. Unlit skiffs are about, almost impossible to detect on radar and heading from A to B at high speed with who-knows-what onboard. What if one of them is packed with explosives and the attack on the tanker is just a diversion? How quickly can we get our helicopter airborne? Having another pair of eyes in the sky, not to mention a rather large gun, will be a huge advantage even if this turns ugly. If it’s up already, what is its endurance? Do I need to get it back, alter to a flying course (which might be heading the wrong way and will almost certainly be across a shipping lane) and refuel it so that she is at maximum endurance as we enter the fight? I need to get on the radio and start issuing warnings. Should I go in at the rather refined, “vessels in this position, this is British Warship, what are your intentions?” or go straight to, “Iranian vessels threatening British Merchant Vessel, turn away or I’ll engage”. If they ignore that and I have to put warning shots in the water, where are those rounds going to end up – there are ships everywhere…

As with any military commander approaching or in a fight, the key is to impose order on the chaos. Are they going to attack the tanker? Will they switch targets to me when I get there? Are they trying to shepherd it into Iranian waters so that they can arrest the crew? Are they going to try and board it to the same end? Or is this just a test: “let’s see what HMS X does in response to scenario Y then back off before it escalates”, something that happens in that area all the time. Most of the time there is no way of knowing. All you know is that there are 220 people onboard whose lives depend on you working it out pretty quickly and a geopolitical tinderbox awaiting you if you get it wrong.

HMS Montrose got it exactly right last week using a mix of speed, awareness and the threat of force to diffuse the situation in much the same way that the Royal Navy has been doing there for decades and elsewhere for centuries. Once the situation is diffused, all that remains is another call to the HQ in Bahrain (making it sound like it was never that hairy), write it up for the analysts, drop a couple of lines home to let them know that it definitely wasn’t that hairy and then get your head down. Just another day as the captain of a warship.

This article was written by Commander Tom Sharpe, OBE RN (Retd) and first appeared on Communications and Military. Tom spent 27 years in the Royal Navy, 20 of which were at sea. He commanded four different warships; Northern Ireland, Fishery Protection, a Type 23 Frigate and the Ice Patrol Vessel, HMS Endurance.

Related articles

- Iran’s illegal seizure of a British tanker – a failure by the Royal Navy or a failure of strategy?

- The Royal Navy and escalating tensions in the Arabian Gulf

- HMS Duncan sent to strengthen the slender Royal Navy presence in the Gulf

- From Sea Wolf to Sea Ceptor – the Royal Navy’s defensive shield

in Analysis / Guest Articles 63 comments Post tagsArabian GulfFrigates

Article and images courtesy of Save the Royal Navy, a privately-funded website dedicated to preserving and enhancing the capabilities of the Royal Navy.

Comments on Chokepoint Charlie – What it’s like to operate a warship in the Strait of Hormuz